1. Olivier Chadoin, Sociologie de l’architecture et des architectes [Sociology of Architecture and Architects] (Marseille: Parenthèses, 2021), 149; Nathalie Lapeyre, Les Professions face aux enjeux de la féminisation [The Professions in the Face of the Challenges of Feminization] (Toulouse: Octares Éditions, 2006), 57–89; Nicolas Nogue, Les Chiffres de l’architecture, t. 1 : Populations étudiantes et professionnelles [Key Figures of Architecture, t. 1, Professional and Student Populations], Paris (Monum: Éditions du patrimoine, 2002), 16–7.

2. The numerus clausus system was nevertheless reinstated for a few years, from 1978 to 1984. See Daniel Le Couédic, “Groupements professionnels” [Professional Bodies], in L’Architecture en ses écoles. Une encyclopédie de l’enseignement de l’architecture au XXe siècle [Architecture through its Schools. An Encyclopedia of the Teaching of Architecture in the Twentieth Century], ed. Anne-Marie Châtelet, Amandine Diener, Marie-Jeanne Dumont, and Daniel Le Couédic (Châteaulin: Locus Solus, 2022), 393–6.

3. Unless otherwise specified, the data presented in this article comes from the thesis I will be defending in January 2023: Stéphanie Bouysse-Mesnage, “Les Pionnières : architectes en France au XXe siècle. Les femmes, élèves du troisième atelier d’Auguste Perret à l’École des beaux-arts (1942-1954)”[The Pioneers: Female Architects in France in the Twentieth Century. Female Students in Auguste Perret’s Third Workshop at the École des Beaux-Arts (1942–1954)] (PhD diss., Université de Strasbourg, 2023), under the supervision of Anne-Marie Châtelet.

4. Louis Callebat (ed.), Histoire de l’architecte [History of the Architect] (Paris: Flammarion, 1998).

5. Maxime Decommer, Les Architectes au travail. L’institutionnalisation d’une profession, 1795-1940 [Architects at Work. The Institutionalization of a Profession (1795–1940)] (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2017).

6. The following is a list of some key works on the topic: Bénédicte Chaljub, La Politesse des maisons. Renée Gailhoustet, architecte [The Politeness of Houses. Renée Gailhoustet, Architect] (Arles: Actes Sud, 2009); Meredith Clausen, “L’École des beaux-arts : histoire et genre” [The École des Beaux-Arts: History and Gender], EAV. École d’architecture de Versailles, no. 15 (2009–2010), 52–61; Élise Koering, Eileen Gray et Charlotte Perriand dans les années 1920 et la question de l’intérieur corbuséen : essai d’analyse et de mise en perspective [Eileen Gray and Charlotte Perriand in the 1920s and the Question of the Corbusian Interior: An Attempt at Analysis and Perspective] (PhD thesis, Université de Versailles-Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, 2010); Stéphanie Mesnage, “Éloge de l’ombre” [In Praise of the Shadows], Criticat, no. 10 (Fall 2012), 40–53; Lydie Mouchel, “Femmes architectes, ‘une histoire à écrire’” [Female Architects, “a History that Remains to be Written”] (diss. in sociocultural history, Université de Versailles-Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, 2000).

7. The French National School of Fine Arts has gone by a number of different names over the years. We’ll be using the most generic name, as well as the commonly used acronym, Ensba (which stands for École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts) in this article.

8. See in particular Carole Lécuyer, “Une nouvelle figure de la jeune fille sous la IIIe République : l’étudiante” [A New Figure of the Young Woman: the Female Student], Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire, no. 4 (1996).

9. See Isabelle Conte, “Les femmes et la culture d’atelier à l’École des Beaux-Arts” [Women and the Workshop Culture at the École des Beaux-Arts], Livraisons d’histoire de l’architecture, no. 35 (S1 2018), 87–98.

10. See Gwladys Chantereau, Les Femmes ingénieurs issues de l’École centrale pendant l’entre-deux-guerres [Female Engineers Trained at the École Centrale during the Interwar Period] (Master’s diss. in contemporary history, Université Sorbonne Paris-Nord, 1997). Note, however, that Ecp teaches many specialties, and construction is only one among many.

11. We’re using their birth names here. The following female architects went by different customary (married) names: (Jeanne) Besson-Surugue, (Thérèse) Urbain, (Adrienne) Gorska-de Montaut / de Montaut, (Jeanne) Bessirard, (Lucia) Creangă, (Yvonne) Meyer-Severt. We do not know the birth name of (Andrée) Garrus, and this is therefore a customary name.

12. The French National School of Decorative Arts has gone by a number of different names over the years. We’ll be using the most generic name, as well as the commonly used acronym, Ensad (which stands for École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs) in this article.

13. The spelling of the name and surname of this female architect isn’t consistent across data sources. She's referred to as Vallia Nicolakaki in the Ensad archives, but as Vassia Kiaulinas or Vassia Kiaulenas in the archives of the Order of Architects of the Île-de-France region (Archives de Paris, 2327W/25).

14. Florence Lafourcade, L’Architecture à l’École des arts décoratifs. Regards sur l’évolution d’un enseignement : de la culture générale artistique à la formation de l’architecte diplômé (1831-1942) [Architecture at the École des Arts Décoratifs. Perspectives on the Development of a Syllabus: from a Foundation of Artistic Knowledge to the Training of Graduate Architects (1831–1942)] (PhD diss., Université de Strasbourg, 2021), p. 484–5. Under the supervision of Anne-Marie Châtelet.

15. See Decommer, Les Architectes au travail, op. cit.

16. Born Renée Bocsanyi.

17. Born Juliette Mathé.

18. See Koering, Eileen Gray et Charlotte Perriand dans les années 1920 et la question de l’intérieur corbuséen […], op. cit.

19. See in particular Mary Pepchinski, “Desire and reality : a century of women architects in Germany,” in Frau Architekt. Seit mehr als 100 Jahren: Frauen im Architekturberuf / Over 100 Years of Women in Architecture (Tübingen: Wasmuth Ernst Verlag, 2017), 25–35.

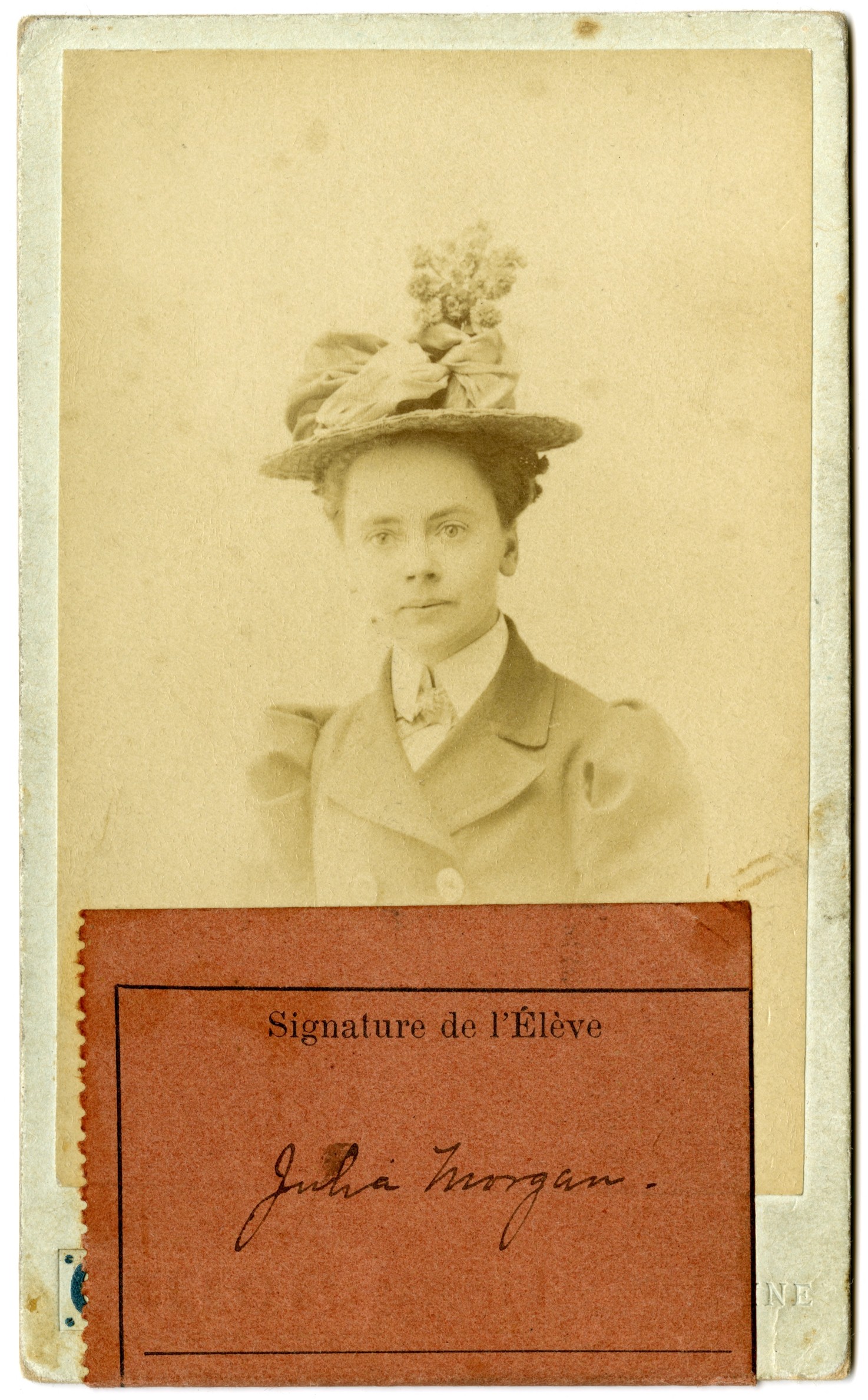

20. Anna Autio, “Signe HORNBORG,” in Le Dictionnaire universel des créatrices [The Universal Dictionary of Female Creators], ed. Béatrice Didier, Antoinette Fouque, Mireille Calle-Gruber (Paris: Des femmes, 2013).