In lecture V of his seminar on “The Object of Psychoanalysis,” Jacques Lacan introduces the notion of the “stumbling block” (butée).* Displaced, it can generate another notion and express what we are attempting to figure out by examining the spatial dimension of care, or what we may call a care function of architecture—and, more broadly, of space: “… contrary to what is said, it is not experience that makes knowledge progress. It is the impasses in which the subject is put because of being determined I would say by the jaws of the signifier. If we grasp proportion, measure, to the point of thinking—and no doubt quite correctly—that this notion of measure and that it is man himself, man has made himself, says the pre-Socratic, the world is made in the measure of man.”[1]

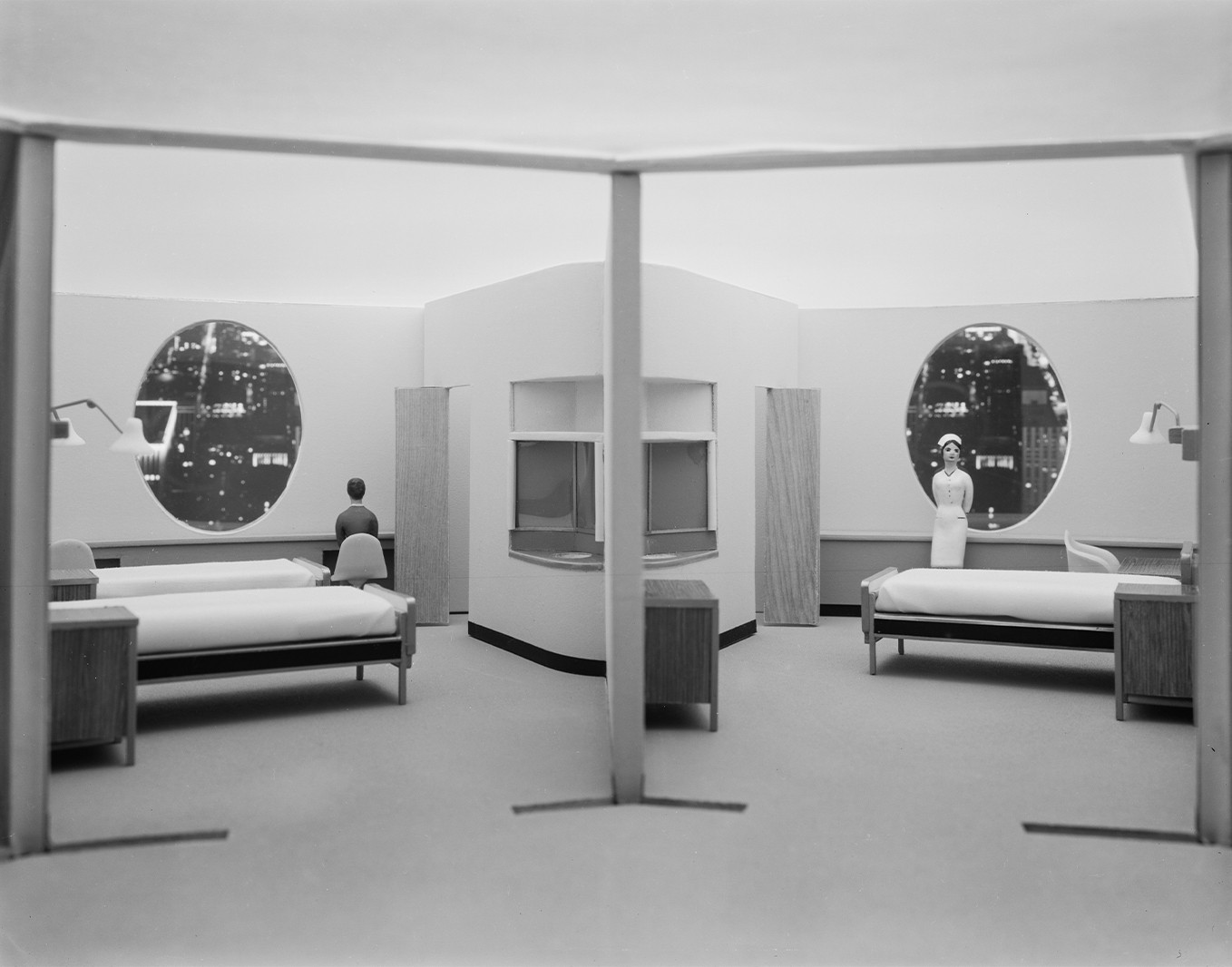

In the lecture, Lacan posits “the ego (is), a function of miscognition,” rather than a “function of the real.” He lays down the “toron,” the hole, and what is played out on the “edge,” as if he wanted to make visible and to capture in a sensory yet also mathematical way what is played out between the subject, desire, the unconscious, reality, neurosis, in other words, what is played out as psychoanalysis and as knowledge. Holes, impasses, aporias, stumbling points (points de butée) (this last concept being constructed by Lacan based on that of perspective, which is indispensable to painting and architecture) are defined here as the very materiality of knowledge. We could then embrace this and open it towards that of “stumbling places” (lieux-de-butée) or “stumbling areas” (espaces-de-butée), in order to be able to mentally construct what is lacking, what escapes synthesis (precisely this reality). Yet, we must nevertheless grasp it and attempt to make this reality inhabitable, even though it will never be conclusively so. Therefore, in order to posit architecture as a thought that progresses from the stumbling places (of these places in which forms, devices, built structures, houses, hospitals, or derelict sites will take shape or not), it is in these places where vulnerability acts as leverage because it leads to a deadlock, and in these places where vulnerability is a stumbling point, specifically allowing a thinking of care that doesn’t show off (as Lacan could have put it) to emerge.

We therefore needed to look for these “toron places” (lieux-tores), these “hole places” (lieux-trous)—in other words, for stumbling points on the surface of the planet. There was also this other inspiration drawing to some extent from the UN system. Falsely pragmatic, yet nevertheless efficient, it consists in placing biodiversity hotspots on the surface of the planet (which are supposed to act as regulators sustaining universal ecosystem services). Here too, the step to the side was a simple and fairly intuitive one—establishing a map of vulnerability hotspots was definitely possible; it wouldn’t be as thorough as the one drawn up by the United Nations, yet it could give us a way of conceiving, seeing, and “architecting” a different world than the one that is offered to us and that most us consider exceedingly unequal and “depriving.” By establishing this map of vulnerability hotspots, it may be possible to devise smarter models accounting for greater complexity and sensitivity to the singularity of situations, which would help generate formulas for habitability—ways of inhabiting the world that rest on the insights uncovered at the edges of these stumbling places. By taking care of these places, by understanding what is at play there as a deficiency, as a deficit, as a neurosis of the world, it could perhaps be possible to upgrade global governance and make it smarter and more efficient, where it had previously demonstrated a consummate competence for falling short of its objective. Was there even an intention to achieve anything else? There emerges a possibility of beating the system at its own game: to use its own tools and to make them more poetic, yet nevertheless operational. If we were to start tracing this map, there would surely be the various circles of Fukushima, given how much they teach us about the intersectionality of industrialism and climate deregulation—if it isn’t simply one and the same thing. It is a prime example of an Anthropocenic place, that could deliver a great many messages and protocols to the future in order to get us out of this now irreversible deadlock. There could also be a rare earth mine, which forms an exemplary stumbling area to compel architectural science in its diversity to generate livable spaces. Within a more Western-centric history and in greater resonance with the topic that we are discussing here, stumbling places where an institutional approach to care was constructed could also be included. Places of psychiatric care have put a rather great emphasis on this requirement of a “place-based” approach to clinical care (clinique du lieu).