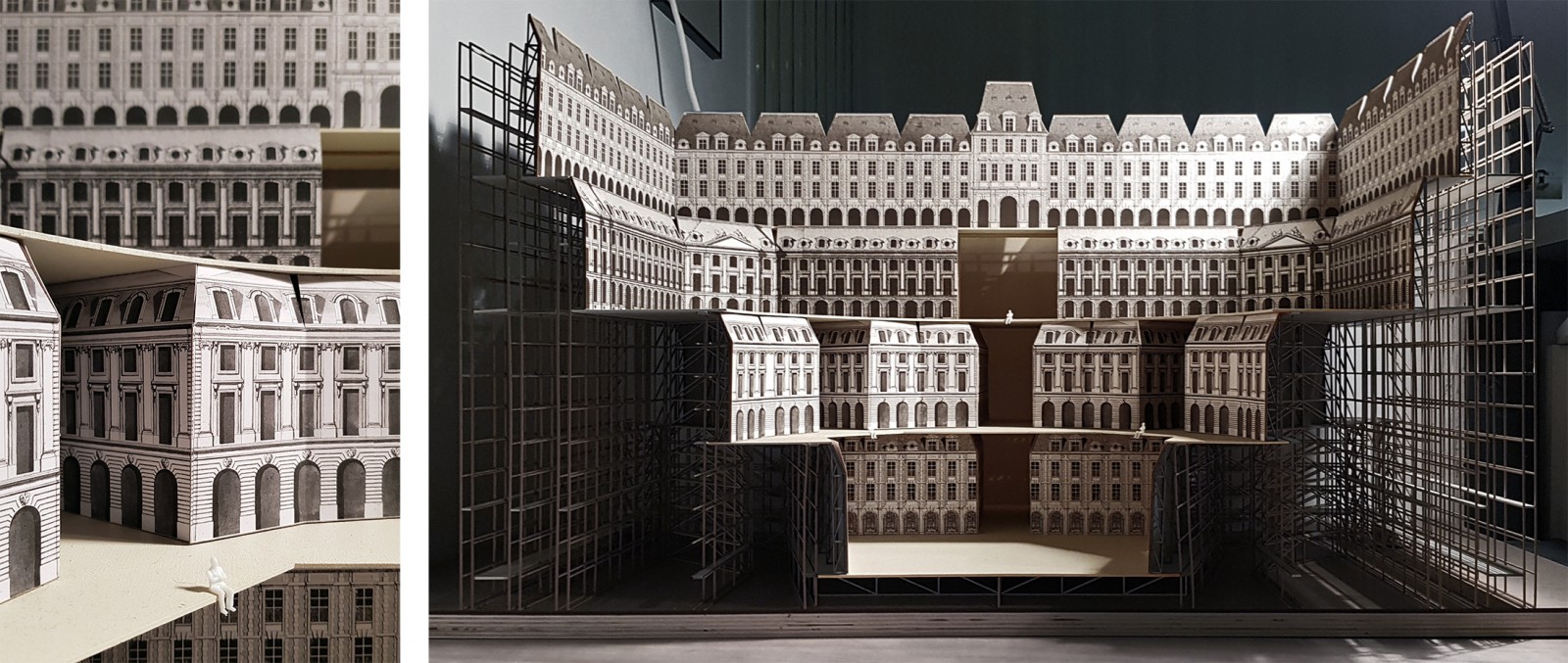

Can architecture be an apparatus [1] for emancipation? I don’t simply mean a style or a symbol of liberty, but truly an apparatus, in the sense of a scenic or strategic arrangement similar to certain artistic or military installations that influence our individual or collective actions. If I ask myself this, it is because architectural and urban planning projects are increasingly rarely able to escape the demagoguery of consultation processes and the tyranny of public opinion.

They seem above all intended to validate dominant discourses and justify the political bodies that commissioned them. They bring possibilities to a standstill rather than open them up. Can we then imagine an architecture that allows individuals, users, residents, or visitors to temporarily take control over them to change their destiny? Can we conceive of architecture in such a way that it brings about other values or a different mode of governance than the one that preceded it? Not by becoming more amenable, flexible, easily appropriated, or participatory—as we are keen to imagine a democratic architecture these days—but, on the contrary, by being determinant in both its form and its way of arousing the desire for debate and occupation.