"Forma, beauty. Beauty is form. A strange and unexpected proof that form is substance. To confuse form with surface is absurd. Form is essential and absolute; it springs from the very guts of the idea. It is beauty; and truth is manifest in all that is beautiful."

Victor Hugo

The Beauty of Necessity

The Jourdan Chris Marker university residence, Owner: Logis transport, RATP Group / Project manager: Eric Lapierre Expérience, Architects. © Filip Dujardin

Septembre 4, 2021

Septembre 4, 2021

16 min.

16 min.

City over Esthetics

The discussions at the time focused more on the city than on architecture itself, and it seemed that esthetic issues bubbled up more when discussing the buildings rather than the city, which itself was generally the focus. In Paris, discussions of a more technical nature or related to landscaping were being discussed as opposed to the purely esthetic. Indeed, Loyer and the drafters of the land use plan of 1977 always insisted on the global coherence of the urban landscape and on the forming of homogenous groups of buildings. They therefore devoted considerable attention to controlling heights and abiding scrupulously to them and without thought to street alignments, thus safeguarding this kind of coherence of landscape. The Haussmanian period that inspired them indeed shines unrivalled in its capacity to create a coherent urban landscape. The architecture itself, however, was only of limited importance. In Haussmann’s opinion, the urban logic always dominates the architectural logic, which is reflected, for example, in the forced decentering of the dome of the commercial court to make it the vanishing point of the perspective towards the south of Boulevard de Strasbourg and Boulevard de Sébastopol, or, simply, the relatively massive architecture of the Haussmanian building itself, which of course does not reduce in any way its unparalleled ability to create coherent urban organisms.

The 1977 urban planning scheme has upheld this relative withdrawal of architecture for the benefit of the whole that characterized a large part of French architectural philosophy over the final thirty years of the twentieth century. In 1987, Bernard Huet wrote a famous article entitled “Architecture against the city [1]” in which he contrasted the city(a collective work carried out over the long run and, as such, supposed to act as the purveyor of core values) to architecture (a private activity of the short term, and thereby considered almost suspect). These analyses, based on a biased reading of the theories of Aldo Rossi, are key to why architecture has long been regarded as forming part of a whole, and not as a form that, whatever its capacity, has its own unique, free-standing features.

Form as a Purveyor of Values

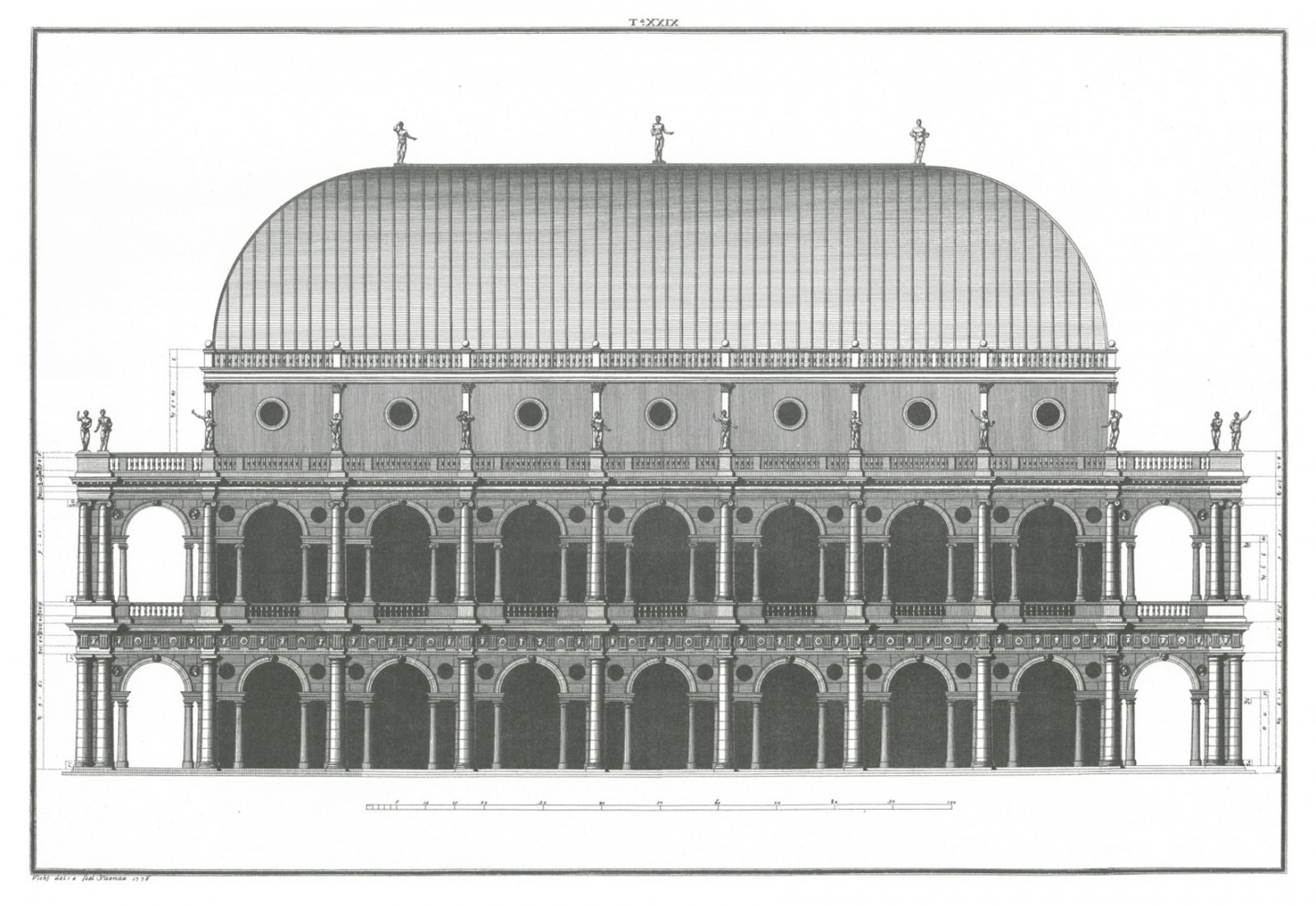

Facade of the palladian basilica de Vicence, dite Palazzo della Ragione (Italie), Andrea Palladio, architect, 1549-1614.

Facade of the palladian basilica de Vicence, dite Palazzo della Ragione (Italie), Andrea Palladio, architect, 1549-1614.

Environmental Virtue, An Opportunity for Architecture

Architects will have to do with less technical means and a larger set of constraints. This situation represents a unique opportunity for architecture in general and for the esthetics of Paris in particular.

The drastic constraints of the architectural response to the environmental crisis form a rare opportunity to rebuild the architectural disciplines in a way that would serve the esthetics of a future Paris well.

Let us first make a few assumptions.

First, that the matching decline in procurable energy sources and existing resources will result in a general reduction in available means that can be used for building purposes [2].

Then, let us posit that architectural rationality aims to produce, through the project process, both a building as a built form and the theoretical and conceptual narrative that establishes the ground rules for creating this form. At the same time, it confers special meaning on it. In other words, the ultimate function of the project process is to create a theoretical narrative, a conceptual context that makes it possible to rationally justify, within the limits of a given project, provisions which would be irrational in another context. The art of the architect consists in imagining productive contradictions that will make his work meaningful, and then to solve them through appropriate reasoning. The particular poetics of architecture rely on this resolution. Such an approach opportunistically accommodates any new necessity of any kind in order to turn it into an expressive element.

The colorful façade of Centre Pompidou on Rue du Renard, for example, would be ridiculous if it were made only of fake tubes—and even if actual tubes had been moved outwards of the building on the architects’ whim. However, the fact that the structure and the main circulation, which are generally located within buildings, is also brought outside, adding to the legibility of the steel framework. This tells us that the device aims to produce a plan freed from all subjection, which is immediately understood as a possible solution for a place dedicated to contemporary art.

Rogers and Piano wanted to make a building that looked like a machine—as if Cedric Price’s Fun Palace had been finally produced. Based on the analysis of the data on the site and the program, they constructed the narrative that enabled them to justify this initial desire. The disruptive nature of the building is fully in line with a history of French and Parisian architecture. This constructive rationalism is defined by Viollet-le-Duc as the possibility of basing the architectural expression of a building on the means employed to produce it. And the co-visibility between Centre Pompidou and Notre-Dame de Paris further reinforces this connection.

Due to the fact that the productions are located in the public space and fit into the flow of an architectural culture that is under continuous reworking, architecture must exemplify collective values. The condition of intelligibility of its products rests on the economy of means. This consists of dedicating the minimum amount of resources to a given task—as required by the contemporary environmental condition. It is also an esthetic category that realizes the possibility of creating relevant forms [3]. The drastic constraints of the architectural response to the environmental crisis form a rare opportunity to rebuild the architectural disciplines in a way that would serve the esthetics of a future Paris well.

A Shareable Architecture

With the economy of means, therefore, being at the crossroads between the environmental response and architectural esthetics, the sustainability of architecture lies well beyond mere technical responses and questioning the very nature of the medium. In order to be sustainable—that is to satisfy a series of quantifiable environmental criteria while equally remaining relevant over time (as accomplished works are)—the architecture of a future Paris will have to pose esthetic questions such as the one raised by Reverdy.

The Specific Character of the Esthetics of Paris

In spite of its wide spectrum of types and landscapes, and the severity with which Haussmann sometimes tacked his network on the existing urban fabric, Paris nevertheless is in no way a brutal collage. Its overall colorimetry and its primarily mineral façades produce a rhythm across the landscape of Paris and there are very few collisions. Even Boulevard Raspail and Rue Réaumur, two of the most demonstrative roads of the city, blend in a sort of unity. Even buildings with an openly modern style, such as the headquarters of the Fédération française du bâtiment designed by Raymond Lopez and Raymond Gravereaux on Rue La Pérouse, the headquarters of Agence France-Press by Robert Camelot and Jean-Claude Rochette on Place de la Bourse, or Jean Nouvel and Emmanuel Cattani’s Fondation Cartier on Boulevard Raspail fit into the Parisian landscape through their rhythms and materials. These works rely on the historic force of Paris and restore it via reasoned novelties. This unified heterogeneity, which is highest in terms of type and relatively lacking in terms of form and colors, is certainly what characterizes best the esthetics of Paris.

Could we speculate on the esthetics of a future Paris?

The depletion of natural and energy resources, as well as the necessary minimization of the carbon footprint of construction represents a paradigm shift worthy of comparison to, in the nineteenth century, the advent of steel and glazing that led to the revolution of the modern movement and the reinvention of space. It would be wrong, however, to view the current situation as the mere end of modernity and its abundance of inventions, and as a step backwards. The limitations given by this new emergent reality, and the social consensus on the necessity of addressing the environmental crisis most certainly represent an opportunity to reconnect with the greater narrative that architecture has been missing in recent years. Addressing this paradigm shift is also an opportunity for Paris to reinvent its esthetic in a way that is consistent with its own history.

The new environmental constraints offer many opportunities to experiment with polymorphic devices that are also new. First of all, they concern the relation to ventilation and natural light and, therefore, questions relating to the composition of plans and volume, the relation of rooms one to another, the relation between the inside and the outside, and so on. These questions are related to that of the ability of the buildings to change over time—to withstand time—and the design of the structures as well as the distribution of fluids in space therefore also need to be considered. Can a change of function easily be accommodated in the future? These questions are connected to that of lifestyle and comfort. Currently, the standards of comfort relating to indoor climate—that buildings must meet rest on the idea of a “perpetual Spring,” consisting in creating an atmosphere in the temperature range of approximately 20 to 27 °C—requires heating or cooling almost year-round, whatever the geographic zone under consideration. These climatic impositions bear a direct influence on the building design and have repercussions both in terms of space and energy use. A greater acceptance of warmth and cold would bear substantial preservations of resources and energy. Not heating or cooling all rooms equally for instance, would also provide spatial solutions to these questions

The current approach is to try to achieve comfort standards that come from the modern world. In terms of acoustics, wooden constructions must, for example, meet requirements that are easily achieved when building with concrete, which is a material that we know is not environmentally friendly. Achieving a level of performance defined based on the use of concrete currently penalizes the use of wood, due to its much lower density—mass being the main factor limiting the propagation of airborne noise. To ensure compliance with these acoustic constraints, the standards, therefore, lead to building hardwood floors so thick that they verge on profligacy, and also often implying doing away with a floor in order to fit in with the standard urban templates, thereby bringing down the profitability of such constructions. The issues of urban regulations are therefore also impacted. Likewise, fire safety standards, which are highly adverse to the use of wood, increase cost and lead times. Paris is, nevertheless, largely built using wood, be it in its lath and plaster walls or the hardwood floors of Haussmanian buildings. We now need to revise applicable standards in light of environmental priority. The philosophy that prevails stems from the technical means of the twentieth century, which has demonstrated both its functional efficiency and its incapacity to respect the environment and resources.

Construction, space, typology, adaptability, in-depth reflection on the economy of means, drafting standards, re-evaluating the idea of comfort, and, beyond that, of our lifestyles, as well as social significance of the whole, shows us the environmental paradigm shift imposes a global rethinking of the definition of architectural forms and their social significance. In the past, the advent of steel and then of glazing revolutionized architecture and led to the complete re-evaluation under which the modern movement emerged. We are currently at the very beginning of a change of the same order, which will involve profound, polymorphic changes, as we have already seen. This normally takes time, however, all markers signal that we have already delayed for too long. Given its size, its aura and its power, Paris could become the experimental field for this paradigm change. A new esthetic will no doubt emerge, which will form part of the historic flow of the city, if only because the materials capable of replacing concrete relate, to a large extent, to the static and tectonic world of the load-bearing masonry that accounts for a large part of the façades of Paris.

To retain the generosity and the convenience of space inherited from modernity, all the while adapting the production system to new requirements will require the invention of hybrid structures.

In the book "La beauté d'une ville" published by the Pavillon de l'Arsenal in 2021.

Éric Lapierre

Éric Lapierre is an architect, professor, theoretician, writer, and curator. His practice’s production, Experience, is an award favorite. His activities—construction, teaching (at EPF Lausanne, ENSA Paris-Est, Harvard GSD), writing—make him a significant participant in the international architectural debate.

1. Bernard Huet, “L’architecture contre la ville” [Architecture against the city], AMC, no. 14: 11 (December 1986).

2. On this topic, see Sébastien Marot, Agriculture and Architecture: Taking Tthe Country’s Side. Barcelona: Polígrafa/Lisbon: Lisbon Architecture Triennale, 2019.

3. Pierre Reverdy, Nord-Sud : Self Defence et autres écrits sur l’art et la poésie (1917-1926) [Self-Defense and Other Writings on Art and Poetry (1917–1926)]. Paris : Flammarion, 1975, 111.

4. Pierre Reverdy, North-South: Self Defence and Other Writings on Art and Poetry (1917-1926), Paris: Flammarion, 1975, p. 111.