After decades of division between cities and agriculture within the framework of sectoral development policies[1], at a time when urgent environmental action is needed, the recurrent crises of urban and agricultural systems compel us to rethink the relationship between farmland and urban society. As dispersed metropolises[2] are absorbing increasingly larger agricultural areas—75% of France’s agricultural potential according to the 2010 agricultural survey and the INSEE statistical office’s zoning of urban areas—large cities which “do not self-produce the food that sustains them”[3] are now being referred to as “naked cities”[4] or “hungry cities,” “new combinations that do not preclude them from conflicts and contradictions but that bind them ever more strongly”[5] are being identified everywhere on the path towards agri-urban development.

The Île-de-France Metropolis

in Agriculture

Market gardening, Herr streat, Paris 15th, around 1900. © Union Photographique Française / Musée Carnavalet - History of Paris / Roger-Viollet

February 26, 2022

February 26, 2022

20 min.

20 min.

From an Agriculture at the Service of the City to Urban Preeminence

The Triumphant City

But, in the early twentieth century, this synergy experienced rapid change under the double transformation—both agricultural and urban—and the development of efficient and rapid means of communication. On the one hand, polyculture, which had been the norm to that point, started being phased out by regional specializations based on climatic and topographical conditions, as fruit, vegetable, and flower cultivation become the appanage of southern France while the loamy plateaux of the Parisian Basin focused increasingly on cereal crops thanks to the emergence of mechanization, transport ensuring ulterior redistribution. On the other hand, the urbanization of Île-de-France crept in sooner in the valleys, especially along the railway lines, colonizing the fragmentary smallholders plots of the ever decreasing market-garden belt. Though World War 2 and food shortages led to land being brought back into cultivation, including within the very heart of the French capital, as in the Luxembourg Gardens, the trend bounced back after the war and then picked up speed. Special crops accounted for only 28,000 hectares in 1955, mostly concentrated in the Seine-et-Oise département, along the Seine valley.

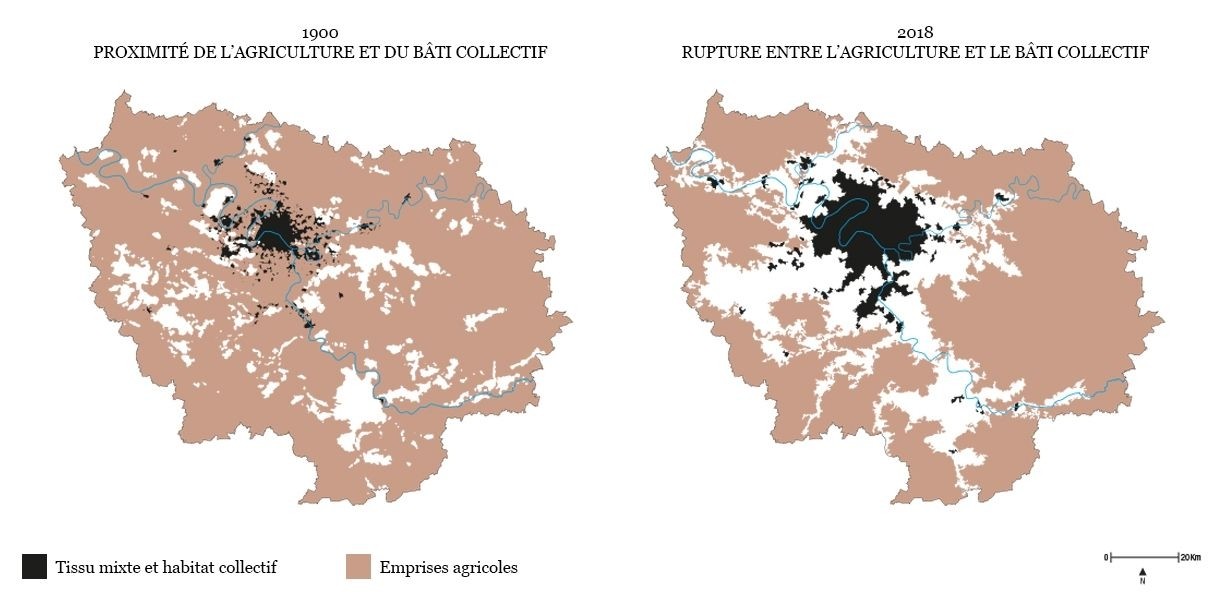

In 1900, the proximity between agriculture and collective buildings made it possible to feed city dwellers and organize the recycling of their waste. In the aftermath of the Great War (First World War) the city was organized by functional sectors with a view to military reconstruction. Even today, the traditional city footprints and the mixed fabrics concentrating collective life are separated from cultures by a set of monofunctional zones: large housing estates, housing estates and economic activity zones. © DR

In 1900, the proximity between agriculture and collective buildings made it possible to feed city dwellers and organize the recycling of their waste. In the aftermath of the Great War (First World War) the city was organized by functional sectors with a view to military reconstruction. Even today, the traditional city footprints and the mixed fabrics concentrating collective life are separated from cultures by a set of monofunctional zones: large housing estates, housing estates and economic activity zones. © DR

From Landscape Grievances to Agriurban System

The Ruralization of the City and the Urbanization of Agriculture

The aggiornamento nevertheless remains challenging given how much the ways of developing the city and the agricultural countryside have diverged, and how strongly economic constraints are continuing to weigh on the situation. Regardless, some forms of redevelopment of agricultural lands can be spotted both in the center—gardens and projects of tower farms, as in Romainville—and in the periphery of the Parisian conurbation, as can be seen in most cities today[17]. Productions and constructions exist side by side, as farming operations supply markets or city dwellers directly through new forms of short supply chains, with producers that self-identify as professionals or hobbyists. The desire for agriculture thus materializes within the city and leads to its ruralization. To a certain extent, as was the case with the mountains and its “sublime horrors,” and then with the “territory of the void” of the seaside[18], sublimated and given value to first by the affluent classes and then by the whole population with the advent of mass leisure, agricultural spaces are in the process of being discovered, appreciated, and included in collective representations as strategic areas that must be preserved and valued. They thus appear as one of the disappearing borders in this movement towards the taming and publicization of places, identified by historians from the eighteenth century onwards. This desire for agriculture is paradoxically rooted in the periurbanization that has transformed the Île-de-France metropolis for the past thirty years or so: all surveys that are conducted indeed reveal how attached the residents of periurban areas are to rural forms—from the fields to the meadows, and the low density—all serve as guarantors of a better quality of life[19]. Overvalued in the rhetoric of local residents and with acknowledged relevance, agriculture provides a set of references, both explicit and implicit, to the natural characters of our living spaces, to a certain connivance with the environment, to a way of life with firm local roots. The desired agriculture is urged to reconnect with proximity, cutting loose of the separation logics that prevailed in the context of productivist agriculture. Also on the agenda is the implementation of diversification strategies to replace the extreme specialization that had been dictated by the quest for the lowest possible production costs, and more broadly, the reconciling of economic and territorial considerations, economic and landscape considerations, or even heritage, economical, and social considerations. Several types of agriculture thus attract a wide consensus: first and foremost a local, quality agriculture to feed the city itself, with marketing channels ranging from farm-gate sales and the AMAP farm basket scheme to open-air markets; it is also an agriculture that is open to the development of forms of reception (pick-your-own operations, educational farms, and so on); furthermore, it is a service agriculture (providing technical services as well as social services, working on better integrating vulnerable sectors of society); finally, it is an agriculture contributing to the environment (upkeep of certain spaces such as the areas around airports, ponds, and swales to mitigate flood risks, and so on). In this new taming between agriculture and local residents, gardens, which had been endowed only with a purely recreational value during the first ages of periurbanization, are now shifting towards a value in productive use; helping (re)create bonds between a living environment and its human inhabitants, it is conducive to a reciprocal acculturation between practices and urban and rural socializations.

AEV’s recent operations, which increasingly involve agricultural land, embody these new directions: in 2016, farmland represented 45% of the acreage of the fifty-five Perimeters for Regional Intervention on Land Ownership, and 2,244 hectares of Utilized Agricultural Area (UAA) were purchased[25] by the Île-de-France region and leased on a long-term basis to a hundred and twenty-five farms. This newly constructed property portfolio, though amounting to only 0.3% of the UAA of Île-de-France, demonstrates the shift in the region’s policy, which aims to “sustain and support agricultural production and its branches ... by providing greater clarity to farmers.[26]” Its recommendations are based on a regional food balance index—the estimated production–consumption ratio–that averaged 1.7% for dairy, 2% for poultry, 3.9% for fruit, 21.8% for vegetables (with the exception of lettuce, at 158%), and 120% for bread-making wheat[27]. Such an imbalance calls for “shifting certain agricultural areas towards local food production …[focusing] in particular towards garden market production, in order to foster short food supply chains[28]”. Far from opting for a heritage garden-market belt to be preserved, the Île-de-France region is aiming for a belt that must be extended and made workable by active interventions under its direction, through the safeguarding of land, the maintaining or restoring of upstream and downstream agrifood industries, and supporting new marketing channels.

The desired symbiosis makes it very clear that the “divide between dense city and periurban, or even rural, spaces” is to be overcome, given that “large agricultural areas … contribute towards urban intensity as well as remarkable landscape openings.[29]” To the now standard city-as-nature[30] trope is now shifting towards the city-as-countryside or even the city-as-farmland, where agricultural land and built-up areas and form together part of the spread-out city[31]. Crucially, various territories are expressly identified as anchor points for future agriurban constructions: these are first and foremost the five natural regional parks (two new ones are in the project stage), but also the unique formula of the agriurban[32] territories along the Green Belt. The project for the park located in Val d’Orge, on the former air base of Brétigny (in the Essonne département), gives a comprehensive summary of the approach :

The agricultural purpose of the site must be upheld and enhanced. Its central portion will be dedicated to organic market gardening over an area of 90 hectares. An urban front will split the former air base into two areas: to the north and west, land reserves for future urban development and open spaces to be preserved to the south, partly used for agrifood research. The eco-site project must ensure that a strategic project is set out … limiting urbanization and fostering its integration in the landscape [33].

These proposals highlight the logic of sharing spaces and designates domains for the transactions between stakeholders looking for a collective agriculture-based project, from the drawing-up of the territorial unit to the cultivation specifications and the ways the built environment and agriculture will come into contact.

The new SDRIF master plan and the various regional programs on food and agriculture include these items while asserting not urban or agricultural systems but agri-urban systems as the key modality for the sustainable city and agriculture of the future. This form belongs to the long history of agriculture in Île-de-France given that it tends to restate both the former garden-market belt and the urban spread by revisiting the urban fronts present since the 1976 SDAURIF: it occurs in places that had already been selected by the very first studies of the Institute for Urban Planning and Development of Île-de-France (IAU—Institut d’Aménagement et d’Urbanisme) as key sectors for agricultural, environmental, and urban reasons, and is a reminder of the weight of central planning in Île-de-France. This historical thickness explains to a large extent the relays provided by civil society in the territorialization of agriurban forms that, once simply possible or latent, are becoming coveted and active. Indeed, the diachronic analysis of recent history highlights the importance of transaction processes between stakeholders. The quest for meaning does not seem to be a problem anymore given how much the visions of a post-carbon city and a renewed agriculture now underpin all projects. However, the difficulty lies in the triumph of an urban vision of agriculture as it is then most often reduced to market gardening, short food supply chains, and sometimes even to 100% organic systems and urban farms. Agricultural value chains are not less agriurban in principle than proximity farming however: both generate landscapes; both can take on a civic role through the hosting of educational visits, front-line social services, or service delivery for local authorities; finally, short food supply chains can complement value chains. This is, in a nutshell, Paula Nahmias and Yvon Le Caro’s proposal, which makes urban agriculture an “agriculture that is carried out and experienced in a conurbation by farmers and residents at the scales of everyday life and the territory covered by the urban regulation. In this space, agricultures—be they carried out by professionals or hobbyists, geared towards long or short food supply chains, or domestic use—maintain functional interconnections with the city, giving rise to a variety of agriurban forms that can be observed in urban cores, peripheral districts, the urban fringe, and the periurban space.[34]”

In the book "Capital agricole" published by the Pavillon de l'Arsenal in 2019.

1. See Monique Poulot, “Des arrangements autour de l’agriculture en périurbain : du lotissement agricole au projet de territoire” [Arrangements Concerning Agricultural in Periurban Contexts: From Agricultural Allotments to Territory Policy], VertigO – la revue électronique en sciences de l’environnement 11, no. 2 (2011) – http://vertigo.revues.org/11188.

2. French research tends to use the idea of “dispersed” or “scattered metropolises” (métropoles dispersées or éclatées) whereas Italian literature favors that of thecità diffusa, and German literature that of the “in-between city” (Thomas Sieverts, Cities without Cities: An Interpretation of the Zwischenstadt, 1997; first published in English in 2000).

3. François Ascher, Les Nouveaux Principes de l’urbanisme. La fin des villes n’est pas à l’ordre du jour [The New Principles of Urban Planning. The End of the City Isn’t on the Agenda], (La Tour-d’Aigues: Éditions de l’Aube, 2001).

4. I’ll mention two recent publications on this topic: Sharon Zukin, Naked Cities. The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), and Carolyn Steel, Hungry City. How Food Shapes Our Lives (London: Vintage, 2006).

5. Martin Vanier, “La relation ville/campagne ré-interrogée par la périurbanisation” [The Urban–Rural Relationship Re-Examined ], Cahiers français no. 328 (“Villes et territoires”) (2005): 13–17.

6. See Flaminia Paddeu, “L’agriculture urbaine dans les quartiers défavorisés de la métropole new-yorkaise : la justice alimentaire à l’épreuve de la justice sociale” [Urban Agriculture in Underprivileged Neighborhoods of the New York Metropolis: Food Justice Put to the Test of Social Justice], VertigO 12, no. 2 (2012) – https://vertigo.revues.org/12686.

7. The term couronne périurbaine appeared in the literature toward the end of the 1960s and, in 1996, it was taken up by the official statistics of INSEE, the French statistics office, which defines it as covering all localities around an urban polarity that are both morphologically set apart from it though dependent on it in terms of employment (with at least 40% of its workforce commuting to workplaces located in the core of the agglomeration).

8. There are a variety of definitions reflected in the abundance of special issues devoted to the topic over the past twenty years: Bulletin de l’Association de géographes français (BAGF), 1992; Cahiers de sciences régionales, 2003 and 2014; Environnement urbain, 2012; BAGF, 2013; Cahiers d’agriculture, 2013; Géocarrefour, 2014; Espaces et Sociétés, 2013; Pour, 2014; Spatial Justice/Justice spatiale, 2015; Géographies et Cultures, 2017—, to mention only the most important publications.

9. See Pierre Brunet, Structure agraire et économie rurale des plateaux tertiaires entre la Seine et l’Oise [Agrarian Structure and Rural Economy in the Tertiary Plateaux between the Seine and Oise Rivers] (Caen: Caron et Cie, 1960); Jean Jacquart, Paris et l’Île-de-France au temps des paysans (XVIe-XVIIe siècles), [Paris and Île-de-France in the Age of Peasants (16th–17th centuries] (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 1990); Jean-Marc Moriceau, Les Fermiers de l’Île-de-France[The Farmers of Île-de-France] (Paris: Fayard, 1994).

10. See Florent Quellier, Des fruits et des hommes. L’arboriculture fruitière en Île-de-France (vers 1600-vers 1900), [Of Fruit and Men. Fruit Tree Cultivation in Île-de-France, Approx. 1600 to 1900] (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2003).

11. See Michel Phlipponneau, La Vie rurale de la banlieue parisienne. Étude de géographie humaine [Rural Life in the Parisian Suburbs. A Human Geography Account] (Paris: Armand Colin, 1956).

12. See M. Poulot, “L’agriculture francilienne dans la seconde moitié du XXe siècle. Vers un post-productivisme de proximité ?” [Île-de-France’s Agriculture during the Second Half of the Twentieth Century], Pour no. 205/206 (2010): 163–177.

13. See M. Poulot, “Agriculture et ville : des relations spatiales et fonctionnelles en réaménagement. Une approche diachronique” [Agriculture and the City: Spatial and Functional Relationships in Redevelopment Contexts. A Diachronic Approach], Pour, no. 224 (2014): 51–67.

14. Quoted in Rapport pour le Sdau [Report for the SDAU Master Plan for Urban Planning and Development] (1976), 9.

15. See Christine Aubry, Yuna Chiffoleau, “Le développement des circuits courts et l’agriculture périurbaine : histoire, évolution en cours et questions actuelles” [The Development of Short Food Supply Chains and Periurban Agriculture: History, Current Trends, and Present Issues], Innovations agronomiques no. 5 (2009) 53–67.

16. See Ingo Zasada, “Multifunctional Peri-Urban Agriculture – A Review of Societal Demands and the Provision of Goods and Services by Farming”, Land Use Policy 28, no. 4 (2011): 639–648.

17. See Joëlle Salomon Cavin, Nelly Niwa, “Agriculture urbaine en Suisse : au-delà des paradoxes” [Urban Agriculture in Switzerland: Beyond Paradoxes],Urbia. Les cahiers du développement urbain durable, no. 12 (2011): 3–16.

18. See Alain Corbin, The Lure of the Sea: The Discovery of the Seaside in the Western World, 1750-1840 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994); originally published as Le Territoire du vide. L’Occident et le désir du rivage (1750-1840) (Paris: Aubier, 1992).

19. See Monique Poulot, Claire Aragau, Lionel Rougé, “Les espaces ouverts dans le périurbain ouest francilien : entre appropriations habitantes et constructions territoriales” [Open Spaces in Periurban Western Île-de-France: Between Appropriations by Residents and Territorial Constructions], Géographie, Économie, Société 18 (“Nouveaux regards sur le périurbain”) 2016/I: 89–112.

20. See M. Poulot, “Histoires d’Amap franciliennes. Quand manger met le local dans tous ses états” [Stories of AMAPs in Île-de-France], Territoires en mouvement, no. 22 (2014): 40–53.

21. SDRIF, Île-de-France 2030. Évaluation environnementale. Projet de Schéma directeur de la région Île-de-France [Île-de-France 2030. Environmental Assessment. Draft Development Master Plan for the Île-de-France Region] (2012), 6.

22. Ibid., 66.

23. Ibid., 32.

24. Philippe Perrier-Cornet (dir.), Repenser les campagnes [Rethinking the Countryside] (La Tour-d’Aigues: L’Aube/Datar, 2002).

25. Contract between AEV and the Société d’aménagement foncier et d’établissement rural.

26 Sdrif, Île-de-France 2030 …, op. cit., 154.

27. Sources: Agreste, France AgriMer, Direction régionale et interdépartementale de l’alimentation, de l’agriculture et de la forêt, and trade sources.

28. Sdrif, Île-de-France 2030 …, op. cit., 74.

29. Sdrif, Île-de-France 2030 …, op. cit., Preamble.

30. See Yves Chalas, “La ville-nature contemporaine. La demande habitante à L’Isle-d’Abeau” [Contemporary City-Nature. Resident Demand in L’Isle-d’Abeau], Annales de la recherche urbaine, no. 98 (2005): 43-49.

31. See André Torre, Jean-Baptiste Traversac, Ségolène Darly, Romain Melot, “Paris, métropole agricole ? Quelles productions agricoles pour quels modes d’occupation des sols ?” [Paris, an Agricultural Metropolis? Which Crops and Land Use Practices], Revue d’économie régionale et urbaine no. 3 (2013): 561–593.

32. This is a procedure that exists only in Île-de-France: these are territories that share a common agricultural project. They do not overlap with intermunicipalities and form “project territories,” similarly to the regional natural parks. Around ten programs were certified in 2005; certain have disappeared, others are becoming increasingly well established. There are currently a dozen of them.

33. Sdrif, Île-de-France 2030 …, op. cit., 200. The emphasis is mine.

34. Paula Nahmias, Yvon Le Caro, “Pour une définition de l’agriculture urbaine : réciprocité fonctionnelle et diversité des formes spatiales” [For a Definition of Urban Agriculture: Functional Reciprocity and Diversity of Spatial Forms], Environnement urbain/Urban Environment 6 (2012) – http://journals.openedition.org/eue/437.

Monique Poulot