During the health crisis, as cities were coming to a standstill, the countryside was being repopulated. The young architect Violette Soleilhac views the expedited and enduring arrival of counter-urbanites as an opportunity to breathe new life into deserted rural town centers. This restoration, brought about by new practices, brings together the values of know-how and sharing. Partly because we have to make do, and partly because we have to come together to revitalize the countryside.

Consider latent territories

05/05/2021

05/05/2021

6 min.

6 min.

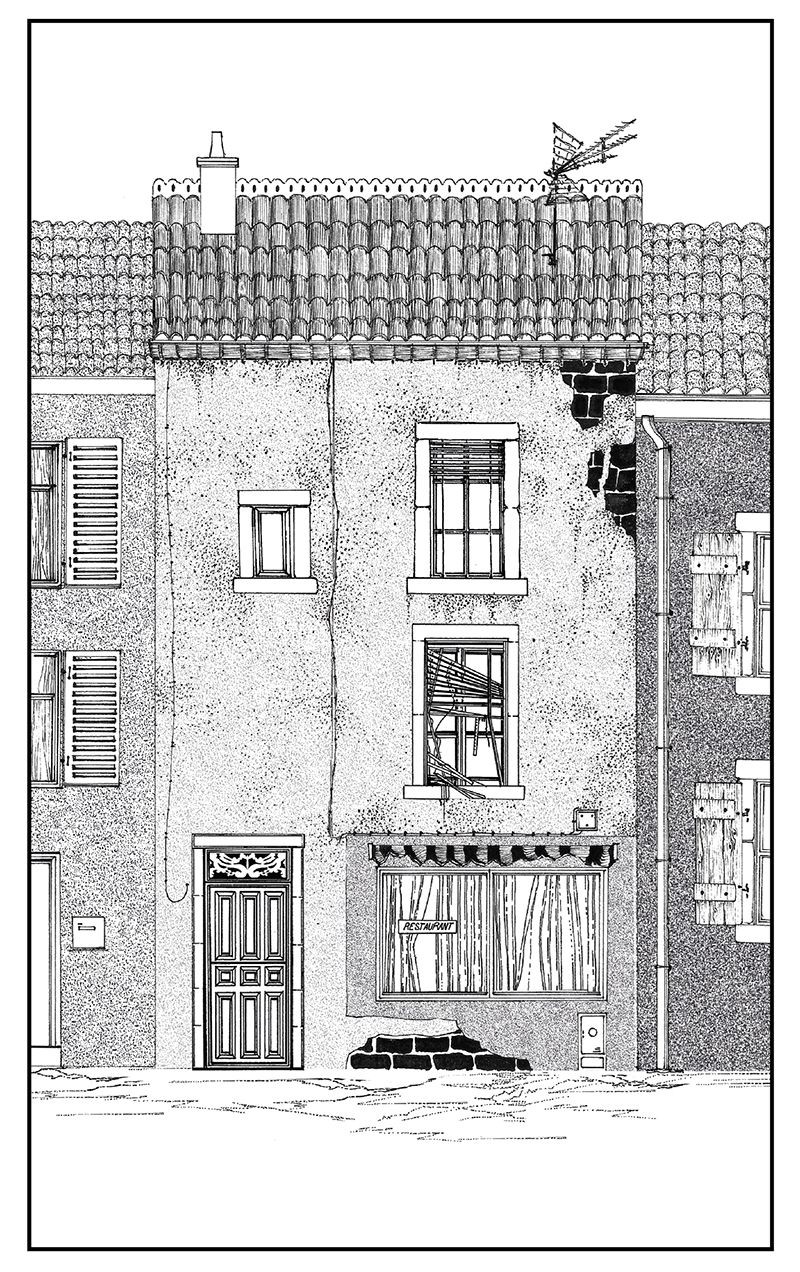

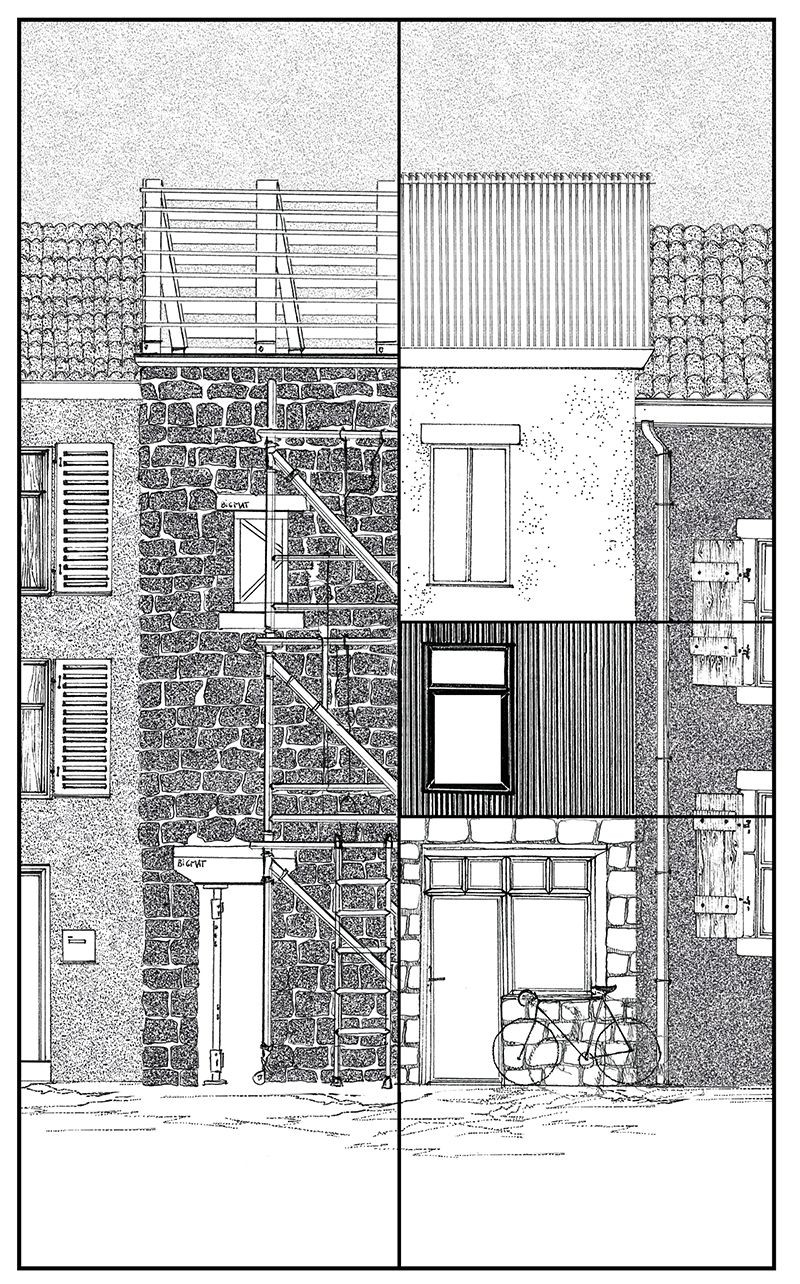

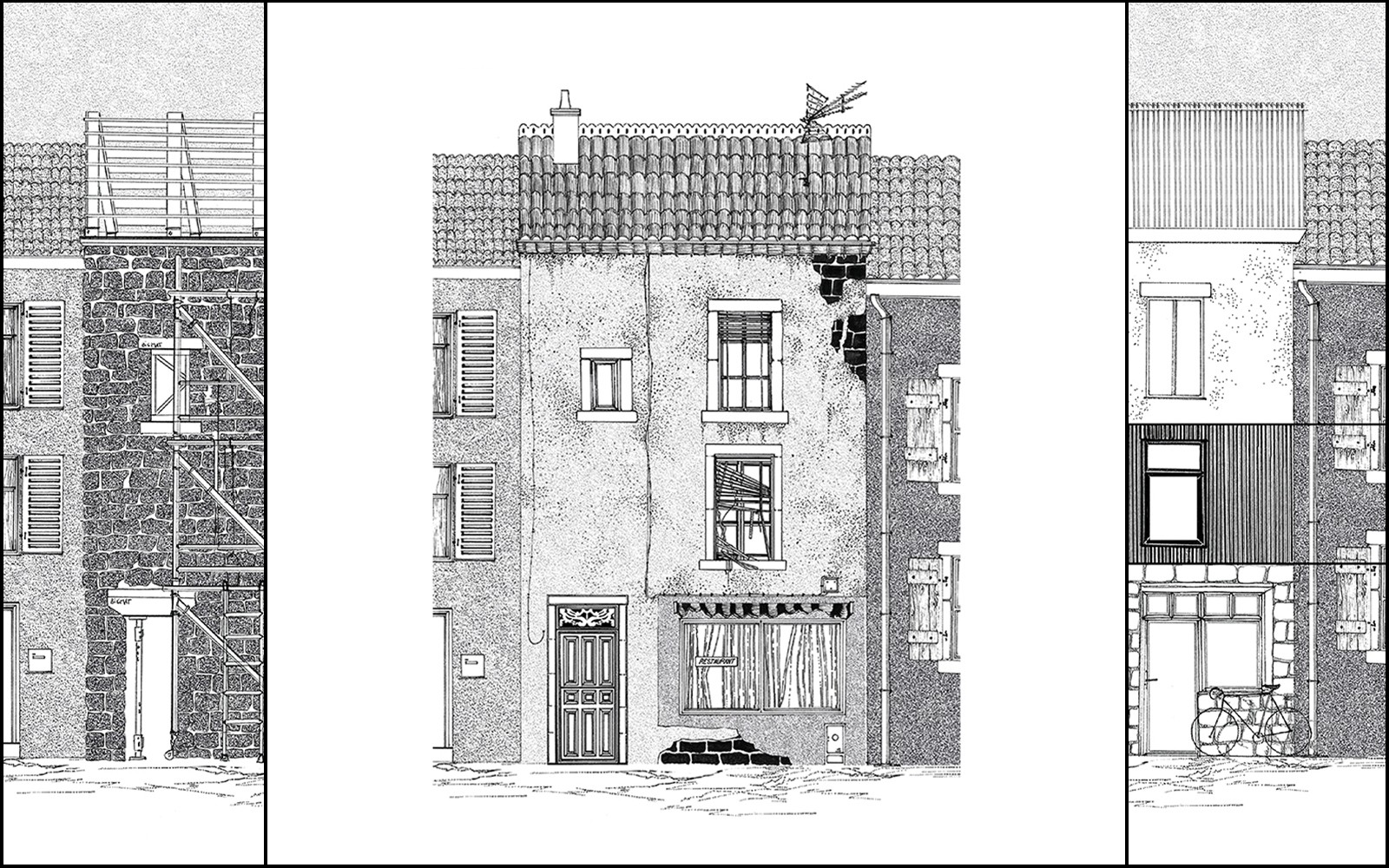

The situation prompts us to reevaluate our habits, pushing us to look more towards rural areas and to give them proper place in the real estate projects of the future. Despite lacking the commercial and cultural offer of the large cities, rural towns carry competitive price tags in terms of housing. But rural demographic growth carries the risk of perpetuating the long entrenched system of urban sprawl. Rural town centers are plagued with high vacancy rates—the small municipality of Alleyrac, in the central Haute-Loire département, is a sad example of this, with its vacancy rate exceeding 21.7% in 2019.[1] It is precisely in these vacant premises that the renewal of rural centralities lies. Even though there will be a need for new housing units, the main issue at stake is that of the transformation and repair of existing buildings.

Indeed, to achieve a diverse offer of housing units to prepare for increasing future demand, it is necessary to first take a stand on which urban orientations should be adopted. What kind of housing will we want in the future? Will we remain within the well-worn model of residential development extending outward from the town centers? Or will we support centralities that are currently almost drained of their inhabitants? In both cases, there will be a real impact on the municipalities, both in the short and long run. But, though certain municipalities are starting to favor the regeneration of their centers, this involves quite some effort, and sometimes even some degree of sacrifice. Choosing to project rural localities from their town centers is to opt for a long-term project. The relevance of these interventions will add up and can only be measured over time, and they extend beyond electoral mandates. It is not a question of immediacy, but of sustainability in the long run. But, as municipalities that have followed that route precociously, the growing number of small projects ends up causing what architect Simon Teyssou calls an “augmented project”[2] to emerge.

Choosing to project rural localities from their town centers is to opt for a long-term project. The relevance of these interventions will add up and can only be measured over time, and they extend beyond electoral mandates. It is not a question of immediacy, but of sustainability in the long run.

So how can the increase in housing projects in these latent environments be spurred? First, it is important to bear in mind the obstacles that rural settings have been facing for many years. For instance, the heritage value of rural towns can actually have a paradoxical effect given that though their uniqueness is appreciated when visiting as tourists, they are snubbed for housing purposes. “It’s pretty, but I wouldn’t live there”—this systematic reaction depicted by novelist Cécile Coulon [3] speaks volumes of the image that these marginalized spaces give. They are too dense, too dark—the suburban model remains very tempting. It is obvious that the gradual abandonment of housing in rural town centers isn’t exclusively due to the all-too-easy alternative of suburbia. This exodus is actually often the default choice due to purchase and renovation costs that are much higher than for new builds. “A disturbing downward spiral sets in: the more the old town centers lose their vitality, the less attractive they become froma housing perspective.”[4]

It is on this sticking point that architects have a large part to play given their capacity to bring together all of a territory’s stakeholders, as well as their problem-solving ethos regarding density, lighting, or overlooking. Renovation represents the largest challenge for the practitioners of the future. It is important to remember that 75% of the housing of the next thirty years is already standing. [5] This is therefore a survey that comes at a time of global uncertainty linked to the Covid-19 crisis, in which our domestic practices are already changing in ways that must be considered in order to imagine what the housing of the future will look like.

Between recent laws, experimental urban projects, and innovative civic initiatives, the possible avenues for action fit within a broad range of adaptations to rural settings relating to housing issues as much as resilience. Three different types of projects stand out. The first type focuses on the buildings themselves, based on which current housing systems are reinvented or even flipped around. The second type calls on programming, i.e., space functionality. The neutrality of spaces must allow for a certain level of versatility in order to better adapt to an increasingly shifting and diverse population. Finally, the third type deals with regulation, aiming to update current laws to make the reuse of existing buildings easier. The end purpose of the projects is not only measured based on the finished architectural products, but also on the ongoing processes used to achieve them.

Half-renovations are a possible response in terms of rural town regeneration projects, as is ‘reverse construction,’[7] gateway housing, intergenerational housing,[8] and rehabilitation leases. This range of possibilities could restore the attractiveness of these places that are said to be ‘dead,’ both in terms of their singularity and their attractiveness. So these places simply exist, in a diffuse way, without being really apparent, and they might, at any moment, reveal their full potential.

1. Diagnostic pour le PLUI de la Communauté de Communes Mézenc-Loire-Meygal [Diagnosis for the Inter-Municipal Local Urban Planning Scheme of the Inter-Municipality of Mézenc-Loire-Meygal], Vol. 1, October 2019

2. Simon Teyssou, “Un urbanisme de fragments en territoire fantôme” [An Urbanism of Fragments in Ghost Territory], Le C.R.I, Territoires fantômes 01:45, no. 1 (December 2019): 45.

3. Cécile Coulon, Les grandes villes n’existent pas (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2015; Large Cities Don’t Exist).

4. “Du centre-bourg à la ville, Réinvestir les territoires, Constats et propositions des Architectes-conseils de l’État” [From Rural Town Centers to Cities, Reinvesting Our Territories, Findings and Recommendations from the State’s Consulting Architects], June 2019: 35. Report for the French Ministry of Territorial Cohesion and Relations with Local Authorities.

5. Erwan Soquet, director of Leroy Merlin Source, invited to Pavillon de l’Arsenal’s September 2019 event in Paris “2049, à quoi ressemblera le logement de demain?” [Housing in 2049: What Will Tomorrow’s Housing Look Like?].

6. “Rendre les logements anciens des centres-villes plus attractifs grâce à des baux dédiés” [Making Older Housing Units from the City Centers More Attractive Thanks to Specific Leases], Bâti j ournal, June 2019. Available in French at the following URL: [http://batijournal.com/rendre-logements-anciens-centres-villes-plus-attractifs-grace-a-baux-dedies/98504].

7. Reverse construction housing project in the municipality of Craponne-sur-Arzon, in the Haute-Loire département in central France, made possible by a renovation lease.

8. Residential development undertaken by Boris Bouchet Architectes in Pérignat-sur-Allier.

9. Idem Note 2.

Violette Soleilhac

After graduating from the École d’Architecture de Clermont-Ferrand, Violette Soleilhac joined Antoine Dufour Architectes in September 2020. She gives particular focus to the issue of renovation in her work alongside Pierre Dufour, chief architect at France’s Historic Monuments office. She also addresses projects in rural settings through written works and studies. In June 2019, she completed a research dissertation concerning the issue of individual housing in rural centers (URL: https://evan-ensacf.com/recherche). She also looked into this topic through her interim year at Fabriques Architectures Paysages, during which she experienced social housing first-hand at the Clément Vergély studio in Lyon, and then at Stanton Williams Architects in London.