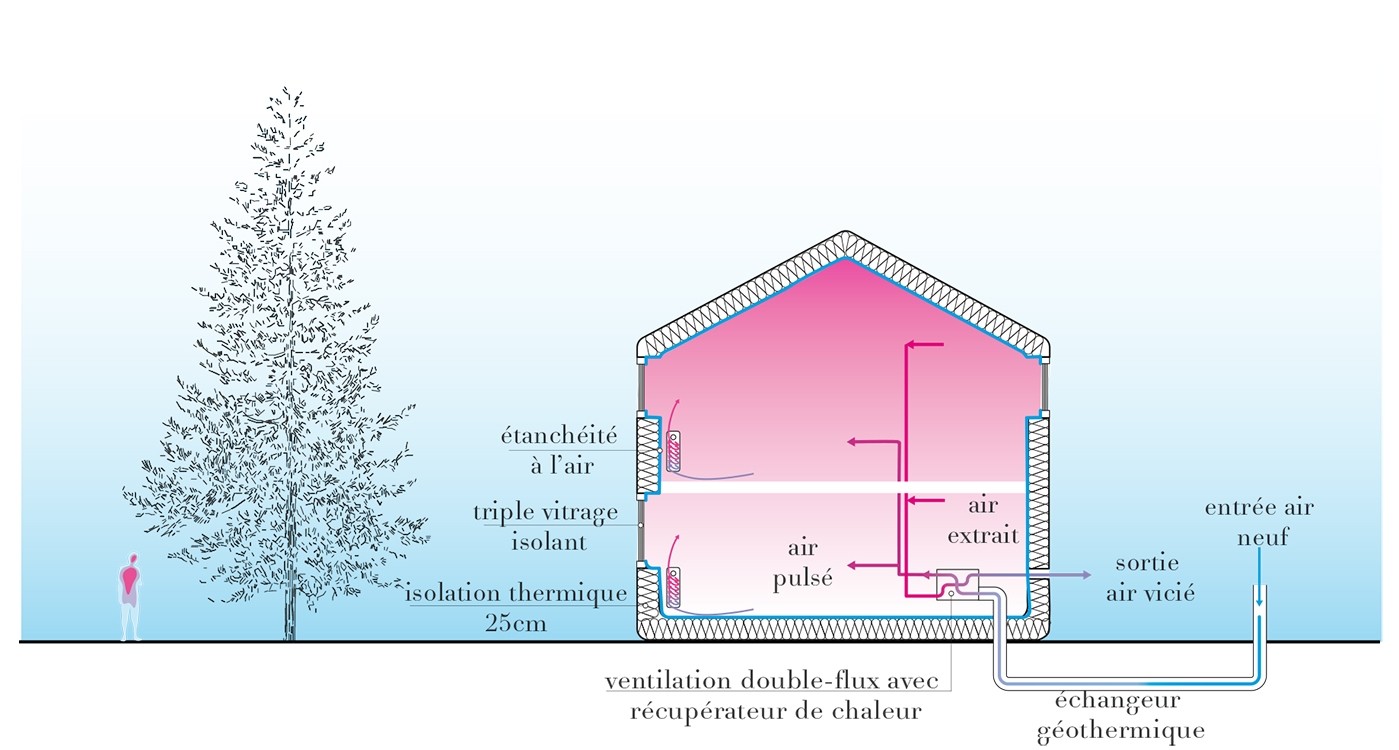

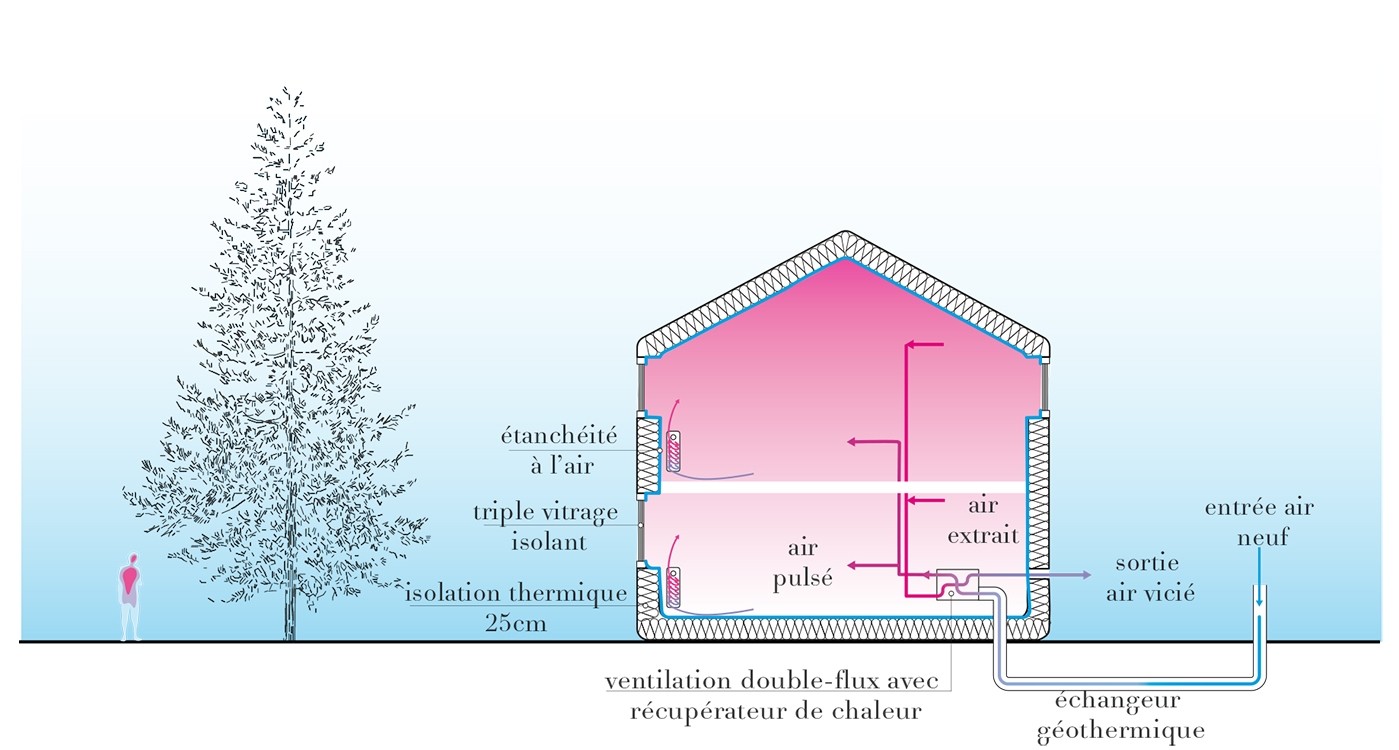

[THE IMPORTANCE OF THERMALLY INSULATING BUILDINGS] Low-energy house. Sources: Minergie-Suisse / Passivhaus-Allemagne © Philippe Rahm architectes, 2020.

[THE IMPORTANCE OF THERMALLY INSULATING BUILDINGS] Low-energy house. Sources: Minergie-Suisse / Passivhaus-Allemagne © Philippe Rahm architectes, 2020.

The sector relating to sheltering of human activities, which can be encompassed under the term of architecture, globally emits 39% of global greenhouse gas emissions, mainly for heating or cooling. By contrast, the aviation industry amounts to only 2%. Architecture is therefore at the forefront in the fight against global warming, which is reflected in the implementation of thermal regulations, new standards and recommendations that as a first step seek to limit energy consumption, which is still 85% dependent on fossil fuels. A new architectural style is now appearing, where the meteorological parameters of space, air, light, heat, humidity, their behaviours and physical characteristics, such as convection, conduction, pressure, emissivity, effusivity and diffusivity, become the new tools of architectural and urban composition.

![[THE EVOLUTION OF ARCHITECTURE IS ASSOCIATED WITH A CHANGE IN AGRICULTURAL TECHNOLOGY] Mars (The month of March). Miniature by the Limbourg brothers for Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, early 15th century, folio 3. © RMN-Grand Palais (domaine de Chantilly) /René-Gabriel Ojéda.](https://mag.pavillon-arsenal.com/data/b4s3_home/fiche/5/media-list_4-1-1_0764e.jpg)

![[AT THE ORIGIN OF SKYSCRAPERS, COAL] Flatiron Building during construction, New York (US). Daniel Hudson Burnham, architect, 1900–1902. Photography by George P. Hall & Son, 1902. © New York Historical Society.](https://mag.pavillon-arsenal.com/data/b4s3_home/fiche/5/media-list_4-3_c756a.jpg)

![[AT THE ORIGINS OF DECORATION] « À mon seul désir ». Sixth tapestry in The Lady with the Unicorn tapestry series, around 1484–1500. © RMN-Grand Palais (musée de Cluny-musée national du Moyen Âge)/Michel Urtado.](https://mag.pavillon-arsenal.com/data/b4s3_home/fiche/5/media-full_5-2_d4259.jpg)

![[FABRIC, A BARRIER AGAINST THE COLD] Princess Mathilde’s Living Room in the Mansion on Rue de Courcelles. Oil on canvas by Sébastien Charles Giraud, 1859. © RMN-Grand Palais (domaine de Compiègne) / Gérard Blot / Christian Jean.](https://mag.pavillon-arsenal.com/data/b4s3_home/fiche/5/media-full_5-1-2_088cf.jpg)

![[THE NATURAL VENTILATION OF PALLADIAN VILLAS] Plan and cross-section views of Villa Almerico (Villa Rotonda), Andrea Palladio, architect, 1566–1571. In I quattro libri dell’architettura, book II, 1570.](https://mag.pavillon-arsenal.com/data/b4s3_home/fiche/5/media-list_6-1_e42f3.jpg)

![[WHEN CITY AIR WAS COAL-BLACK]Factory smokestacks in an industrial city in England. Wood engraving by Roth, circa 1880. © INTERFOTO / Alamy Stock Photo.](https://mag.pavillon-arsenal.com/data/b4s3_home/fiche/5/media-full_7_51201.jpg)

![[PARKS TO LIVE LONG LIVES] Victoria Park, London (UK), Sir James Pennethorne, architect, 1842–1845. Plan showing the proposed layout for Victoria Park, circa 1840. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.](https://mag.pavillon-arsenal.com/data/b4s3_home/fiche/5/media-full_7-1_dc71a.jpg)

![[WHITE MODERNITY VS. CONSTRUCTIVE TRUTH] Villa E-1027, Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, Eileen Gray and Jean Badovici, architects, 1926–1929. In L’Architecture vivante, winter 1929. Bibliothèque d’architecture contemporaine Coll., Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, Paris. All rights reserved.](https://mag.pavillon-arsenal.com/data/b4s3_home/fiche/5/media-list_9-blanche_37690.jpg)

![[URBANIZATION THROUGH THE DISCOVERY OF OIL] Oil derrick in Signal Hill (California, US). Photography, circa 1925. City of Signal Hill, California. All rights reserved.](https://mag.pavillon-arsenal.com/data/b4s3_home/fiche/5/media-full_10bis3_809a2.jpg)

![[AIR CONDITIONING ERASES THE IDIOSYNCRATIC FEATURES OF REGIONAL ARCHITECTURE] Aerial view of the city of Abu Dhabi (United Arab Emirates). Photography circa 1960. Jorge Abud Chami Collection. Courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation.](https://mag.pavillon-arsenal.com/data/b4s3_home/fiche/5/media-full_10bis_083d6.jpg)

![[THE FAILURE OF MODERN SANITARY THINKING] Pruitt Igoe’s residential complex, Saint Louis (Missouri, US), Minoru Yamasaki, architect, 1951–1954. Demolition of a building, 22 April 1972. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. All rights reserved.](https://mag.pavillon-arsenal.com/data/b4s3_home/fiche/5/media-list_11-1_dcc87.jpg)